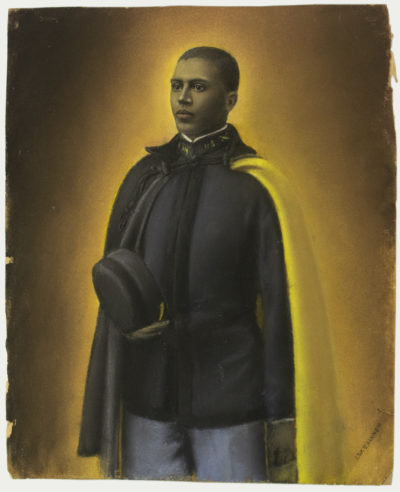

Colonel Charles Young

(1864-1922)

United States Army

Accession number:

2020.02

Maker:

J.W. Shannon

Historical period:

ca. 1884-1889

Miltary branch:

Army

Wars and Conflicts:

American Indian Wars, Philippine-American War, Spanish-American War, World War I

Type:

Pastel, reproduction

Dimensions:

H x W: 11 in. / 8.5 in.

Acquisition date:

March 2020

Credit line:

Courtesy of the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center

Location:

Dining Room, First Floor

Provenance:

From March 2020: The Army and Navy Club, courtesy of the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center

Label:

Charles Young was the third African American graduate of the United States Military Academy, and his inspiring career helped pave the way for African Americans in the U.S. Armed Forces. Among his many unprecedented accomplishments, he was the first African American military attaché, the first African American U.S. national park superintendent, the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel in the Army, and the highest ranking black officer in the Regular Army when he died on deployment in 1922.

Little is known about this unique portrait of Young as a cadet, made sometime during his time at West Point from 1884-1889. However, it provides insight into the esteem in which he was held as a young officer: he wears a golden dress cape and is backlit by a halo of what could be described as divine light. This portrait is likely a pastel drawing over a photograph—a popular portrait technique in the late 19th century.

Young was commissioned in 1889, upon graduation from West Point. He served first with the 9th Cavalry Regiment in Nebraska and Utah before reporting to Wilberforce College in Ohio in 1894. He led the new military sciences department, established by a federal grant that foreshadowed the ROTC program. During his four years on the faculty he became close friends with fellow professor W.E.B. Du Bois. When the Spanish American War broke out, he was put in command of the 9th Ohio Infantry Regiment, the first time in Army history an African American commanded such a unit.

When the Army founded the Military Intelligence Branch in 1904, Young was assigned as one of the first military attachés—to Haiti. Later, he was the first African American attaché to Liberia.

In the early 20th century the Army supervised all national parks, and Young became the first African American Superintendent of a national park, commanding Sequoia and General Grant National parks. Other commands included the Presidio in San Francisco and Fort Huachuca, Arizona. He served twice in the Philippines.

In 1912 Young published The Military Morale of Nations and Races, a remarkably prescient study of the cultural sources of military power. He argued against the prevailing theories of racial character, citing history and social science to demonstrate that even supposedly “un-military races,” such as Negroes and Jews, displayed martial virtues when fighting on behalf of democratic societies. He asserted that the key to raising an effective mass army from among the multi-ethnic American society was to link patriotic service to the fulfillment of equal rights and fair play for all. Young's book was dedicated to Theodore Roosevelt and invoked the principles of Roosevelt's "New Nationalism."

During the 1916 Punitive Expedition into Mexico he commanded 2nd Squadron, 10th Cavalry, leading a cavalry pistol charge against the forces of Poncho Villa, routing the enemy without losing a single soldier.

Young was retired medically in 1917 due to high blood pressure. As an act of protest in June 1918, the retired Lt. Colonel Young made his way 500 miles on horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio to Washington, DC, to prove that he was fit for duty. Once there, he petitioned the Secretary of War for immediate reinstatement and command of a combat unit in Europe. He was reinstated and promoted to full Colonel—the first African American to receive that promotion in the history of the American Armed Forces—but he was assigned to duty at Camp Grant, Illinois. By the time his reinstatement and promotion were in effect, the war was nearly ended.

In 1919 he was reassigned as the attaché to Liberia. He became ill while conducting a reconnaissance mission in Nigeria in late 1921 and was hospitalized at the British hospital in Lagos, Nigeria, where he died on January 8, 1922. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.